Sundiata Keita

Mali’s 13th century unifying king is one of the most sung-about ancient rulers, first of all, of course, by the griots – or more properly, to use the name they give themselves, djeli. The Mandinka epic, which tells the story of the marriage of Sogolon to the ruler of Mali, the birth of Sundiata, his exile, his victory and his reign, is a soap opera from which, for eight centuries now, the guardians of memory and the masters of the word have drawn. It has also inspired many musicians, from Tiken Jah Fakoly to Pepe Kalle who, using both reggae and soukous, have sung Sundiata’s name to remind everyone of the pride that his story represents for the entire continent. Let’s not forget that it was under his reign that the Charter of the Mandé was adopted, a declaration of human rights that preceded the Declaration of the Rights of Man by five centuries.

Among the recorded versions of Sundiata’s story, one in particular has made a mark. This version was created by the Guinean Mory Kanté, with the Rail Band of Bamako, and tells of Sundiata’s exile. When he is chased out of court by his half-brother who has seized the throne, he leaves with his mother to seek refuge with the rulers of the region, until they all unite under his banner to fight Soumahoro Kanté, the king of Soso. The latter holds Gnankouman Doua, Sundiata’s djeli, prisoner. It was Soumahoro who gave him his magic balafon and christened him ‘Balla Fasseke Kouyaté’, thus creating the first ancestral line of djeli. This moment – which Mory Kanté explained to PAM – is also recounted in “Soundiata, l’exil”, a 28-minute piece that manages to wonderfully combine the depth of the story and the sonic temperament of a modern orchestra, with guitars replacing the ngoni and balafon. A must listen.

Zumbi dos Palmares

Four centuries after Sundiata, the Atlantic slave trade was in full swing, emptying Africa of its workforce to cut sugar cane and harvest cotton or coffee on plantations in Brazil, Guadeloupe, Cuba, and Haiti. In every country, those who were enslaved found ways to resist, and those who managed to rebel or flee – known as ‘Maroons’ – reached inaccessible hill areas or the depths of forests and founded communities there. This was the case in Brazil, where in present-day Nordeste (200km south of Recife), the quilombo (free community) of Palmares developed, and where (at around 1655) Zumbi was born.

The community, which later grew to over 20,000 people, also included Indians and a few landless whites. As a child, Zumbi was kidnapped during a Portuguese expedition and handed over to a priest who educated him and baptised him Francisco. At the age of 15 the young man ran away to join the quilombo community in Palmares that was led by his uncle, Ganga Zumba. Zumbi distinguished himself in battles against the Portuguese, who found themselves unable to defeat the Maroons. A treaty of non-aggression was finally signed in 1678 with Ganga Zumba but, like many others, Zumbi rejected it, refusing to allow slavery to continue anywhere in Brazil. Zumbi seized power and continued to resist for almost 15 years, though he was eventually killed by Portuguese forces on November 20th, 1695. The date is still marked in Brazil as a ‘day of Black consciousness’, and statues of Zumbi – the symbol of the resistance and liberation for African-Brazilians – can be found in Rio, Salvador and São Paulo.

It’s not surprising that such a hero has been sung about so often, notably by Jorge Ben, who released the song “Zumbi” in 1974 on the album A Tàbua de Esmeralda. It opens with a list of the regions from which slaves were taken (‘Angola, Congo, Benguela…’) and in two snapshots paints a picture of what slavery looked like: the African princess sold with her retinue at auction, the gentlemen watching the harvesting of the white cotton by Black hands. Each time we hear the haunting refrain: ‘I want to see, I want to see…’ Finally Zumbi, the lord of war and supplication, appears like an orixa (Ogun, the god of war) to deliver the enslaved. The song “Zumbi” was also covered by Caetano Veloso.

Kwame Nkrumah

The pan-Africanist leader has been sung about many times, although the coup d’état (1966) that ended his reign was followed by a long period of silence in Ghana. It must be said that the immediate memories of him at home were quite different from his aura abroad. Nkrumah was a pan-African leader, and his struggle for Ghanaian independence had served as something of a springboard to that ideology. It was to this rise and the hopes it raised that the Trinidadian singer Lord Kitchener, who arrived in London in 1948 shortly after Nkrumah’s departure for Ghana, paid tribute. It was from there that he witnessed the rise of the CPP (Convention People’s Party), the imprisonment, and then the accession to the presidency of the man who would later be called the ‘osagyefo’ – the redeemer. And it was also from London that he sang, just before Ghana’s independence, of the fantastic example of this country which had not only gained independence before all the others in Africa, but which had also become a beacon of hope for Black populations all over the world.

The national flag is a lovely scene

With beautiful colors Red, Gold, and Green

And a Black star in the center representing the freedom of Africa

In the series “Ghana Freedom” PAM gives the full story.

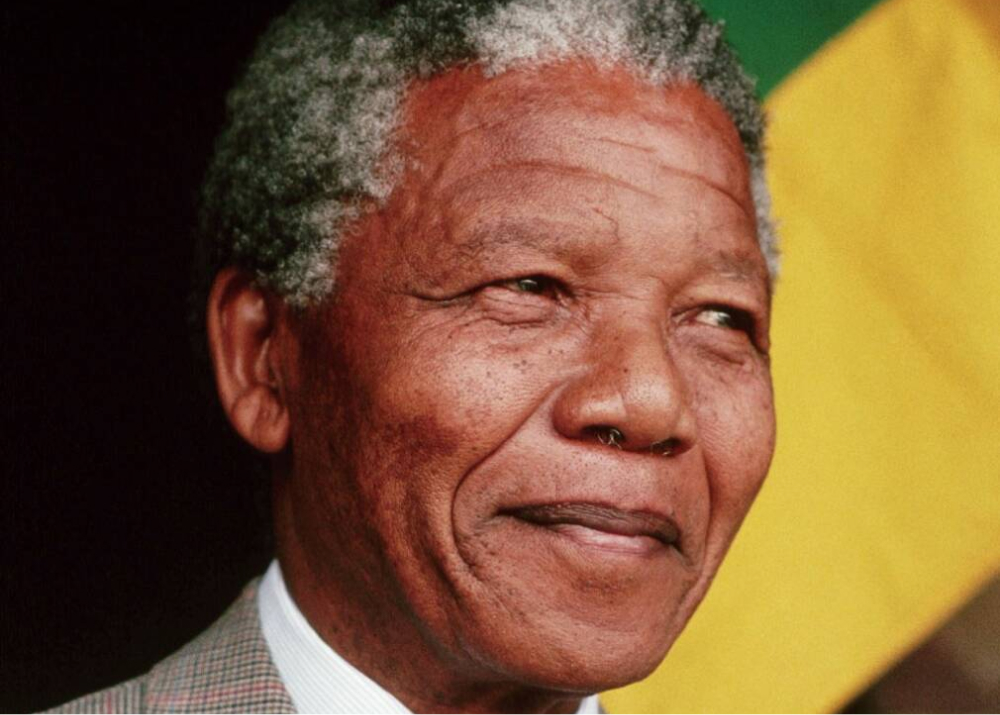

Nelson Mandela

On 11th February 1990, Nelson Mandela, aka Madiba (his clan name) was finally released after 27 years in prison. On the same day, he declared that he would continue the struggle against apartheid, demonstrating a determination and humility that greatly impressed the rest of the world. “I stand before you not as a prophet, but as your humble servant. It is because of your tireless and heroic sacrifices that I am here today.” There is no doubt that Mandela was referring to the daily resistance of a great number of people against apartheid.

Among those who actively campaigned for his liberation, artists played an important role, and this was true whether they were South Africans or not (a concert at Wembley to mark Mandela’s 70th birthday comes to mind). Mandela, during and after his imprisonment, but also after his death, is certainly one of the most sung about figures in African history. From Danyel Waro to Miles Davis, Salif Keita to Burning Spear, PAM has compiled a selection of artists who have paid tribute to him.

Among them, of course, is Johnny Clegg, whose song “Asimbonanga” (we have not seen him) has become an international hit. “My generation, he told PAM, “had never seen what Mandela looked like, and it was a crime to even have a picture of him. Some people went to prison for it. We had never seen him. We knew what he had done, but it was just a name. That was a fact. ‘Asimbonanga, Mandela. We’ve never seen him, where he is, or where they’re holding him.’ That’s all I’m saying.” Mandela would surprise the audience on stage in Frankfurt in 1999 for a moment that would go down in history.

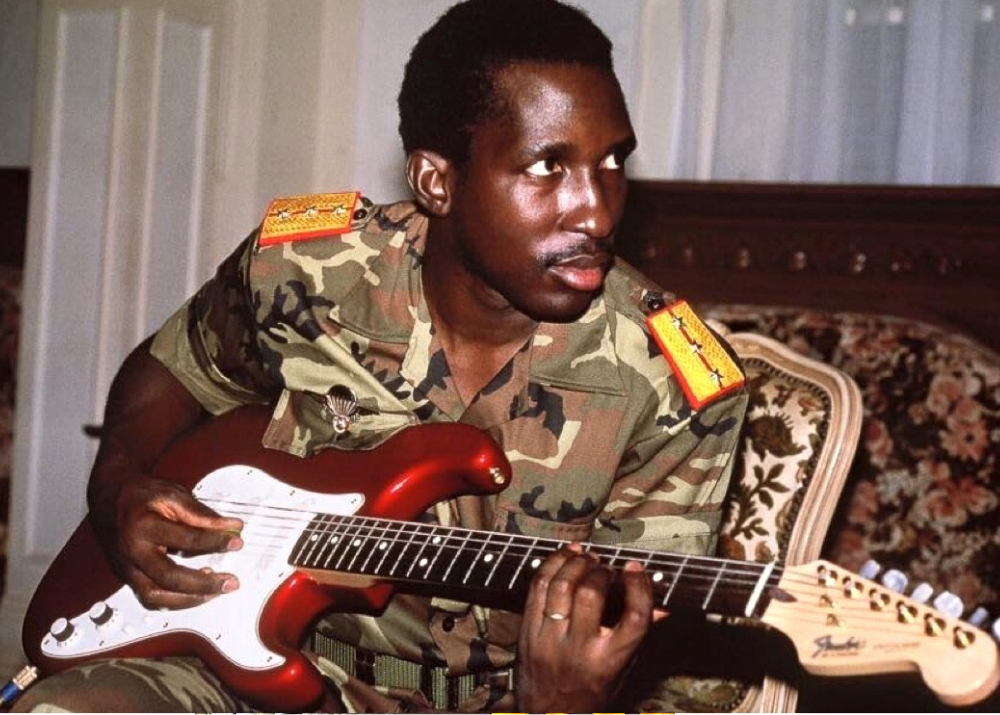

Thomas Sankara

The path of Thomas Sankara, whose presumed assassins are currently on trial in Burkina Faso a quarter of a century after his death, was that of a dazzling comet in African skies, lighting up North-South relations. Nearly 25 years after independence, ‘Tom Sank’ began the struggle for true independence: to consume and produce locally, to refuse to pay back debts, to rebalance relations between rich and poor countries as well as, in Burkina Faso, between men and women… He did so much work that he was nicknamed ‘the African Che’, and pushed forward with his vision, inspiring some and disturbing others – others who would not forgive him. His lofty speech and clear, fair ideas earned him many enemies, both inside and outside the country.

Assassinated on 15th October 1987 at the age of 37, Sankara, who had changed the name of Burkina Faso (the land of incorruptible people) from the colonial Upper Volta, is most notable for the legacy he left behind. This was most vividly demonstrated in 2014 when a popular revolution put an end to the regime of Blaise Compaoré, one of the main suspects in the current trial. During these events, ‘Sankara’s children’ were at the forefront, including the rapper Smokey, spokesperson for the ‘Balai citoyen’ movement, who a few years earlier had recorded a song in tribute to the iconic captain with his Senegalese comrade Awadi, whose studio in Dakar is called… studio Sankara.

Discover all of our Black History Month features.